Ever find yourself in one of those late-night conversations that spirals into a topic you never expected? I was grabbing coffee with a buddy last week, and somehow we got from complaining about our Wi-Fi to arguing about ancient history. He made an off-hand comment about how everything from the ancient world is basically a guess. “How do we really know what Plato wrote?” he asked. “For all we know, we have, like, two copies that a guy in a basement found.”

That question stuck with me. It’s a good one. It got me wondering, and after falling down a rather deep research rabbit hole, I found an answer that honestly shocked me. When you ask the question, how many copies of Plato survived compared to the Bible, you’re not just asking a trivia question. You’re stumbling upon one of the most lopsided stories in the history of the written word.

The short answer? It’s not even close. We have an absolute mountain of biblical manuscripts and, by comparison, a small, respectable hill of Plato’s writings. But the story behind those numbers is where things get really interesting.

More in Bible Category

How Was the Bible Put Together

How Were the Books of the Bible Selected

Key Takeaways

- The Bible Wins by a Landslide: There are over 24,000 surviving manuscript copies of the New Testament alone (in various languages). If you just count the original Greek, it’s nearly 6,000.

- Plato’s Numbers Are Still Impressive (For an Ancient): We have around 210 medieval manuscripts of Plato’s works. That’s far more than most other classical authors.

- It’s About Purpose, Not Popularity: The Bible was the foundational text for a rapidly expanding global religion that believed copying it was a sacred duty. Plato’s works were academic texts, preserved by scholars for a much smaller, more niche audience.

- Time Gaps Are Huge: The earliest bits of New Testament manuscript we have date to within a generation or two of the original authors. For Plato, the time gap between when he wrote and our earliest complete copies is over 1,200 years.

So, What Are the Actual Numbers We’re Talking About?

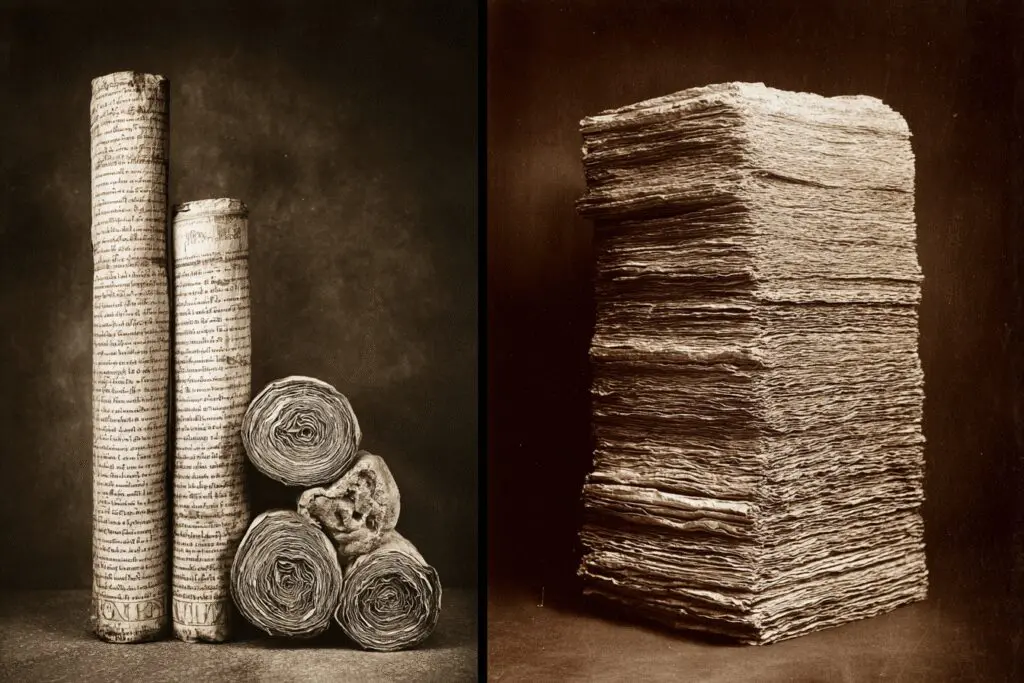

Let’s just get the raw data out on the table first, because it really sets the stage. When we talk about ancient manuscripts, we’re not talking about pristine, leather-bound books that look like they just came from a print shop. We’re talking about fragments, scraps of papyrus, and handwritten parchments that have miraculously survived fires, floods, wars, and simple neglect for centuries.

For the New Testament, the count is staggering.

- Greek Manuscripts: We have approximately 5,800 manuscripts written in the original Greek.

- Latin Manuscripts: Tack on another 10,000 or so manuscripts in Latin (the language of the Roman Empire).

- Other Ancient Languages: Then you add thousands more in languages like Syriac, Coptic, and Armenian.

All told, scholars are working with a library of more than 24,000 manuscript copies of the New Testament. Some are tiny fragments with just a few verses, while others are complete or nearly complete books.

Now, let’s turn to my buddy’s question about Plato. How does the great Athenian philosopher stack up?

We have about 210 medieval manuscripts containing the works of Plato. And to be clear, that’s a fantastic number for any ancient secular author. For most classical writers, you can count the surviving manuscripts on one or two hands. The fact that Plato’s work survived in such numbers is a testament to his incredible influence.

But it’s not 24,000. It’s not even in the same universe. It’s like comparing the number of squirrels in my backyard to the entire cattle population of Texas. Both are impressive in their own right, but they are on completely different scales.

But Why Such a Massive Difference?

Okay, so the numbers are wild. My first thought was, “Well, the Bible must have just been way more popular.” And that’s true, but it’s also too simple. It’s not just about what people liked to read; it’s about why they were reading and copying it in the first place.

The early Christians weren’t just part of a book club. They were part of a movement that believed their texts contained the literal words of God and the secret to eternal life. For them, preserving and copying the scriptures wasn’t a hobby; it was a non-negotiable act of worship and evangelism.

Plato, on the other hand, was writing philosophy. Brilliant, world-changing philosophy, but still, it was for the classroom and the study. People weren’t building communities around Plato’s Republic in the same way. You didn’t have missionaries traveling the globe with copies of his dialogues. The motivation was entirely different.

What Did Copying Look Like for the Bible?

I always had this mental image of a single, solitary monk working by candlelight for fifty years to produce one perfect Bible. That definitely happened, but it was just one part of a much larger, more decentralized preservation machine.

From the very beginning, Christian communities were spread out all over the Roman Empire and beyond. Each of these little church groups needed their own copies of the scriptures for services, study, and teaching. So, as soon as they got a copy of a letter from Paul or one of the Gospels, local scribes would get to work making more.

Was It Like a Giant Game of Telephone?

This is where my skeptical side kicked in. If you have thousands of people all over the world copying copies of copies, wouldn’t you just get a total mess? It seems like a recipe for disaster, where errors and intentional changes could creep in until the original message was completely lost.

Here’s what I found that surprised me:

- The Scribes Were Serious: While they weren’t all professionally trained, the people copying the scriptures believed they were handling sacred material. There was a deep-seated reverence that discouraged casual changes.

- The Sheer Number is a Good Thing: This is the counter-intuitive part. Because we have so many manuscripts from so many different places and time periods, we can cross-reference them. If one scribe in Egypt made a mistake in the 4th century, we can compare his work to a manuscript from Italy made in the 5th century and another from Syria in the 3rd century. Where they all agree, we can be extremely confident that we’re looking at the original text.

- The Errors Are Mostly Minor: Scholars who spend their lives studying these manuscripts say the vast majority of differences are simple spelling mistakes, word order swaps, or the equivalent of a typo. Not a single core doctrine of the Christian faith is affected by these variants.

This whole field of study is called textual criticism, and it’s a fascinating detective story. They’re not trying to defend the text; they’re just trying to figure out what it originally said. Having more evidence, even if it’s messy, is always better than having less.

So Where Were Plato’s Books Hiding All This Time?

Plato’s journey through history was much quieter and more perilous. After the fall of Rome, a lot of the knowledge of the Greek language was lost in Western Europe. For centuries, Plato was more of a legend than a widely read author in places like France or England.

His works were primarily preserved in the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire), where Greek was still the language of scholarship. They were kept alive in libraries and by academics in cities like Constantinople. A handful of his dialogues were also known in the Arabic-speaking world, where they were studied by Islamic philosophers.

It’s a much more fragile chain of transmission. Instead of thousands of communities creating copies, you had a small number of scholars and libraries doing the work. If a fire or a conquest had hit one of those key libraries at the wrong time, we could have lost huge chunks of his work forever. It almost happened several times.

Then How Did We Get Them Back?

The big comeback for Plato happened during the Renaissance. As scholars in Italy began to rediscover classical texts, there was a mad dash to find and translate Greek manuscripts. Think of it like a treasure hunt.

Agents for wealthy patrons like the Medici family scoured the libraries of the crumbling Byzantine Empire, buying or borrowing every ancient manuscript they could find. When these texts arrived in Italy, they were treated like gold. They were copied, translated into Latin, and became the intellectual fuel for the Renaissance.

This is a key point: many of the Plato manuscripts we have today are not from the ancient world. They are copies made in the Middle Ages, often from the 9th century AD or later.

Does a 1,200-Year Gap Matter?

This, for me, was the biggest bombshell.

The earliest little scrap of the New Testament we have (it’s called the John Rylands fragment, or P52) dates to around 125 AD. The Gospel of John was likely written around 90 AD. That’s a gap of maybe 30-40 years. It’s the historical equivalent of me finding my dad’s original notes from his college lectures.

Now think about Plato. He was writing around 380 BC. Our earliest complete manuscript of his work, the Clarke Plato, was copied in 895 AD.

Let that sink in. That is a gap of more than 1,200 years.

Imagine trying to reconstruct your great-great-great-great… (add about 30 more “greats”) …grandfather’s diary based on a copy someone made a thousand years after he died. It’s mind-boggling.

This isn’t to say the text of Plato we have is unreliable. The scribes who preserved it were incredibly careful. But the sheer documentary evidence for the New Testament is on another level. The timeline is just so much tighter. You can learn more about the methods scholars use to reconstruct ancient texts from resources like the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, which digitizes and studies these ancient documents.

So, Is It Just an Apples-to-Oranges Comparison?

At the end of the day, maybe that’s the real answer. Comparing the manuscript traditions of Plato and the Bible is like comparing the flight log of a private jet to the complete air traffic control records for every airport in the world. Both tell a story of a journey, but the scope and purpose are fundamentally different.

- Plato’s Legacy: His work survived because it was considered the pinnacle of intellectual achievement. It was preserved by a small, dedicated line of scholars who knew they were handling something precious. Its survival is a quiet, academic miracle.

- The Bible’s Legacy: Its texts survived because they were the lifeblood of a community. It was copied and re-copied in homes, churches, and monasteries by thousands of ordinary people who believed their eternity depended on it. Its survival is a loud, messy, and populist phenomenon.

The sheer volume of biblical manuscripts doesn’t automatically prove they are “true,” just as the smaller number of Plato manuscripts doesn’t mean they are “false.” But from a purely historical and documentary perspective, there is nothing else from the ancient world that even comes close to the textual evidence we have for the New Testament.

It’s made me realize that when we pick up a modern translation of either Plato’s Republic or the Bible, we are holding the end result of two very different, but equally incredible, stories of survival. And that coffee-shop conversation? It ended with my buddy just shaking his head and saying, “Okay, you win. That’s actually pretty wild.” And it is.

Frequently Asked Questions – How Many Copies of Plato Survived Compared to the Bible

What does the manuscript evidence mean for the faith of believers today?

The extensive manuscript evidence confirms the reliability of the Bible, strengthening believers’ trust in its message and reminding us that God’s preservation of His Word is a meaningful part of history and faith.

What are the key tests used by historians to verify the authenticity of ancient documents?

Historians use internal tests to check the content for historical accuracy, external tests to compare with other sources, and bibliographical tests to analyze the number of copies and the time gap between original and copies.

How does the manuscript evidence for the New Testament compare to that of ancient Greek writings like Plato?

The New Testament has over 5,800 Greek copies and over 24,000 copies in all languages, with the earliest dating within 25-50 years of the original, whereas Plato has only about seven copies with a 1,300-year gap.

Why does the number of manuscript copies matter for the reliability of historical texts?

The number of manuscript copies and the time gap between the original writing and the copies help verify the accuracy of ancient texts; more copies and shorter gaps increase confidence in the text’s integrity.

How many copies of Plato have survived compared to the Bible?

There are only about seven major manuscript copies of Plato’s works, while the Bible has over 5,800 Greek copies alone, and more than 24,000 copies in various languages.